Nathalie Lambert was Canada’s Chef de Mission for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games. She is a pioneer in short track speed skating—first introduced to the Olympic Winter Games in Calgary (1988) as a demonstration sport. Lambert’s team finished third there. In Albertville (1992), short track speed skating was a medal sport for the first time. Lambert’s team won gold. Lambert’s third Olympic appearance, in Lillehammer (1994), yielded two silvers. Lambert won many World Championships, and set many records before retiring from competition (1997). She returned to the Olympic Games as Canada’s Assistant Chef de Mission in Athens (2004), and is a long-standing member of several Halls of Fame: Canadian Olympic, Quebec’s Sports, Canada’s Sports. She has also been named as Athlete of the Year by both the Merite Sportif Quebecois and the Canadian Speed Skating Association. Lambert has been Director of Communications and Marketing at Montreal’s Club Sportif MAA since 1999. She also brings passion for sport and physical activity to motivational speaking, fitness DVDs, and a book. Diagnosed with osteoarthritis, while still speed skating competitively, Lambert became an Honorary Patron of the Arthritis Society of Quebec on retirement. A mother of two, Lambert and her husband live in Montreal.

Alex Baumann is an Officer of the Order of Canada, appointee of the Order of Ontario, and member of the Canadian Sports and Canadian Amateur Sports Halls of Fame. He has an Honorary PhD in Physical Education (Laurentian University) and was World Male Swimmer of the Year twice (1981,1984). Alex swam at the 1984 Olympic Games, winning gold, and setting world-records for both the 200 and 400 metre individual medley races. He won five more gold, and two silver medals, at Commonwealth Games (1982,1986) and two gold, four silver, and six bronze at other Games: World University, Pan Pacific, and World Championship. In 1991, Alex pursued graduate studies at the University of Queensland, Australia, later working for the Queensland Academy of Sport (QAS) and the Queensland Government. From 1999, he was Chief Executive Officer of Queensland Swimming. From 2002, he was Executive Director of QAS, overseeing Athlete and Coach Support Services, Regional Services, and the Centre of Excellence for Applied Sport Science Research. He helped make sure Australian athletes had the best resources to attain optimum podium performance at Olympic and Paralympic Games. In 2007, Alex returned to Canada, becoming Executive Director of the Road to Excellence (RTE) program, now called Own the Podium (OTP). This program aims to re-establish Canada internationally as a leading sports nation with a top 12 finish at the Olympics and top eight finish at the Paralympics (London, 2012). In 2009, Alex became Chief Technical Officer, responsible for all OTP summer and winter technical programming.

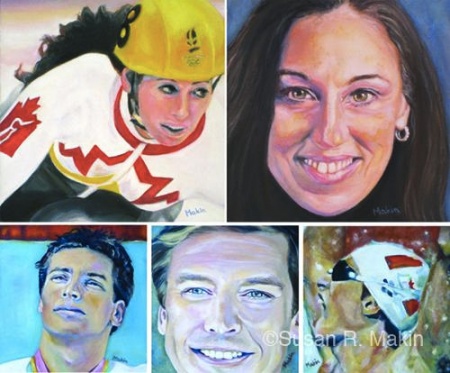

Commentary: Artists, Athletes, Canada

Athletes’ and artists’ bios have much in common. To attain such high standards, reach goals, pursue dreams, and make their country proud, they have had to work very hard and not give up, whatever the challenges. Many have grown up and or trained in other countries, but come to call Canada home. They are thrilled to represent her, winning medals and accolades, locally and internationally. Ways to do this might not, always, have appeared certain, sure, or predictable, and some exceptional folk have had less recognition than they merit.

Even when talent comes naturally, it doesn’t, usually, shine without the necessity of making unusual efforts and sacrifices, giving inordinate amounts of time and resources to help develop and nurture it. And, even with extreme dedication, there are still no guarantees—of reward, recognition, or satisfaction. Winning doesn’t have to be everything. Just being chosen to participate should be enough. But, it isn’t always... Being so close, but yet so far, often without others’ understanding of the efforts made, begs further consideration and attention.

Regardless of outcomes, or how others feel about them, those who are successful in their athletic and artistic vocations know that their journeys are often lonely, long, and hard. Getting juried in and accepted, even without medal or acquisition following, can be arduous. Easier daily routines have to fade into the background: self-discipline, endurance, and persistence being required to take over. Teams and groups may strategize together and have a spirit of camaraderie and fun along the way. But, there are still obstacles: not wanting to let self or others down, or cause embarrassment, may be restrictive, as can having to keep up the pace and not fall behind. Pressure and persistence are ever-present. Responsibility, obligation, and accountability prevail, even when end-results tend to, and or have to, appear flawless and uncomplicated. The simplest objectives, and outcomes can have the most intrigues, detours, and dangers.

Bringing art and athleticism together requires courage, community, and conviction. We know that our sportsmen and women are terrific. Our artists are, generally, a little more hidden from public view—and not just due to the nature of their work, study, or personalities. With Canadian government cuts to arts funding, there just aren’t the mechanisms and support options to help grow talent and have it shine publicly. Canada, as one country, has different modes of expression and accomplishment to show off to the world. History, and popular opinion, more often than not, has Canadians being better known for their sportsmanship than artistic craft/cultural endeavors.

Not unexpectedly, even though these works were painted to raise money for charity, as for most of the other pieces for the Portrait Society of Canada show that year, there were no takers.